Early Monasticism

Early Monasticism

There had always been a strong ascetic element in Christianity that rejected everything associated with the world and worldly life. The history of the Church in the 300s presented that element with a dilemma. In earlier times, such persons were fully at home in the regular Christian community, which stood in theoretical opposition to the state and its worldly concerns. But, in the 300s, that opposition ended and the Church began to acquire such worldly things as wealth and power. Opposition to the state did continue among Christians that were, at any given time, subject to government repression; but they were mostly heretics, outside the mainstream of the faith. Ascetically inclined orthodox Christians could hardly pray for a return to persecution so that they could express their rejection of the world. They had to find another outlet for their asceticism.

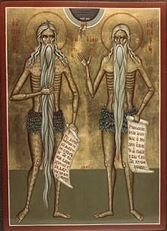

So, the 300s saw the rapid growth of a new movement in the Church aimed at denying the world and its concerns. The man who popularized this movement was a pious Egyptian named St. Anthony (d. 356). He was the first true Christian monk, or really hermit. By steady stages, he gave up his property and worldly comforts and slowly withdrew from normal human society. Eventually, he became a complete hermit, spending all his time in prayer and self-denial.

He set an example for all Christians who found the new prosperity, and, indeed universality, of the Church spiritually disturbing. Many followed in St. Anthony’s footsteps, first in Egypt and then in other parts of the East. Average Christians came to admire such persons for renouncing worldly concerns for the benefit of their souls. In fact, hermits quickly came to replace the martyrs as the great heroes of Christian principle.

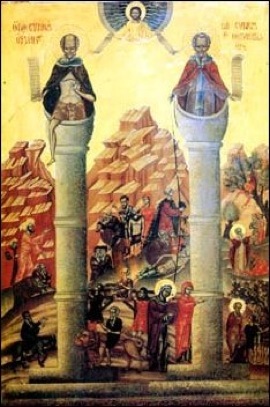

At their most extreme, early monks inflicted far more punishment on themselves than the most ruthless persecutor could have devised. A good example is the Syrian ascetic, St. Simeon Stylites (d. 459). In his early life, he was so famous as a hermit that crowds of people sought him out to venerate him. He sought a novel means to escape from direct contact with them. He moved to the top of a ruined column in the countryside near Antioch and lived there for the last thirty-seven years of his life. It was sixty feet high and three feet around at the top. Believe it or not, he was widely imitated by a whole class of hermits known as pillar saints.

Men like this presented a large and annoying problem for the Church establishment. They were uncontrollable individualists, and there was a danger that their beliefs and practices might come to violate existing Christian norms. There was also a danger that, unrestrained, they might slip into heresy. They were too holy and too popular to suppress, but efforts were made to control them. One way to do that was to organize them in a community with formal leadership and formal rules to follow. Simply put, they could be transformed from hermits to monks.

The first such community was set up by another Egyptian, St. Pachomius (d. 345). Participants gave up personal wealth, withdrew from society, and practiced asceticism like hermits. But, they lived together in a common dwelling on an island in the Nile. Under this arrangement, members could support one another spiritually, work together to satisfy their minimal material needs, and be restrained from doctrinal and behavioral deviation.

The trend toward regulation was further strengthened by St. Basil of Caesarea (d. 379). He wrote a series of works discussing the best practical means of achieving the goals of monastic life. In the sixth century, the Emperor Justinian (527-565) completed the trend by issuing extensive legislation, based on Basil’s theories, to govern the activities of both hermits and monasteries.