The Golden Age of the Polis

The Golden Age of the Polis

The Athenian Empire

The international ascendancy of Athens in the 400s B.C. was a direct result of the continuing conflict between the Greeks and the Persians. Hostilities with Persia did not end with the defeat of the Persian army in 479. The theater of war merely shifted from the mainland to the coasts and islands of the northern and eastern Aegean. Many Greek subjects of Persia had risen in revolt after the battles of Plataea and Mycale; and the allies desired to liberate them and to drive Persian influence from the Aegean altogether. The Spartans took the lead in this effort at first, but they quickly lost interest in pursuing a war so remote from their own land.

After the defeat of their army in 479, the Persians withdrew their forces from the mainland of Greece, but that did not mean that the threat from Persia was ended completely. Persia still controlled the Ionian Greek cities on the coast of Asia Minor just across the Aegean. In this position, it was always possible that they might mount a new invasion of Greece at any time.

For this reason, a number of Greek states decided to set up an alliance to continue the war until Persian influence had been eliminated from the Aegean area entirely. In the winter of 478/477, they agreed to set up a new defensive league for the purpose of prosecuting the war. The participating cities were mainly from the Aegean islands and the northern parts of Greece. Because Sparta did not want to involve her armies in such long-range operations, she and the other members of the Peloponnesian League did not belong.

The headquarters of the league was established on the island of Delos in the center of the Aegean. For that reason, the alliance was know as the Delian League. The league was a military assistance pact similar to NATO.

Each member of the alliance was required to contribute to the military effort according to its means. Large cities gave ships and men for the forces. Smaller cities merely gave money to finance operations. The league members were to meet each year to decide on the strategy for the year to come. Each city had one vote. Since Athens had the largest fleet, she was selected to lead the forces of the League. She supervised the collection of the money, and she furnished the commanders for military operations.

This alliance was extremely successful in its efforts against Persia. By 450 B.C., all of the Ionian cities of Asia Minor had been freed from Persian domination. Persian influence was eliminated. As the Greeks of Asia Minor became free, they too joined the Delian League so that the influence of the alliance gradually grew. And, of course, the influence of Athens, as the leader of the alliance, also grew whenever the league expanded.

The growth of Athenian power in foreign policy was accompanied by a great advance in the internal organization and prosperity of the polis as well. The man most responsible for this progress was Pericles.

The major accomplishment of Pericles internally was the perfection of the Athenian system of democratic government. This system had continued to grow more democratic since the time of Cleisthenes in 508; now it was completed. At some point, probably during the time of Themistocles, the archons, who were the major officers of the state, ceased to be elected. Instead, they were chosen strictly by lot. There was a drawing, and the men whose names came up were archons. Thereafter the only officials who continued to be elected were a committee of ten generals, who led the armies. The generals had to be elected because their jobs were too technical to be left to chance.

Pericles was responsible for two measures that extended democracy even further. First, he eliminated the last property requirements for holding office. Now, any Athenian could be archon if his name came up. Second, he introduced the practice of paying any person who served in public office. This was important because previously, no one received pay for any public service. This meant that poorer citizens often had to work during the assembly meetings. Now they could all serve.

This system was a perfect democracy because every citizen could hope to hold office and to influence the making of policy. If a man was dissatisfied with the way the government was run, all he had to do was got to the next assembly meeting and say so. If enough other citizens agreed with him, they could vote to change things. This meant that a man would could speak well and persuasively in the assembly often had great influence in policy even if he did not hold any public office proper. Such men were called demagogues, which means leader of the demos. Remember that demagogue is not an office. Frequently demagogues were so popular that they might hold the elective office of general. This is how Pericles could be a major leader for thirty years. Many but not all of those years he was general.

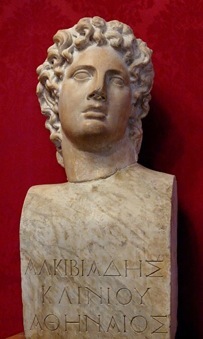

On the Athenian side, the wars did not go well because the assembly made all of the decisions. In a time of crisis, it is difficult to make consistent policies when everybody has to be consulted about them. If Pericles had lived, Athens might have won; but he died in 429, and the later Athenian leaders were not as capable as Pericles. Pericles had always warned the Athenians that they could win if they focused on Sparta and avoided other foreign entanglements. After Pericles died, the state was dominated by another demagogue named Alcibiades. This young aristocrat was a disaster for the city. In 414, Alcibiades convinced the Athenian assembly to undertake an invasion of Sicily to make war on the city of Syracuse. The ill-omened campaign was a catastrophe. The Athenians were defeated and weakened. Additionally, when Acibiades was recalled to Athens, he deserted his native polis and defected to Sparta! He then provided leadership against Athens.

The greatest Spartan problem was that Athens controlled the sea. By the second war, it became evident that Sparta must have a navy to defeat the Athenians. In 412, Sparta made a deal with the Persians to return the Ionian cities to Persia in exchange for money to build ships. That is how the Spartans eventually won out.

The destruction of the political power of the polis was a much more gradual process. It is evident from 404 to 338 B.C. Like many great conflicts, the Peloponnesian Wars disillusioned most of the Greeks who participated in them. Greeks had once believed that loyalty to a polis was the most important feeling that a man could have. But they now saw that such loyalty could lead to terrible destruction. After 404, loyalty to the state is replaced by more personal concerns and interests. Moreover, the example that Athens had set was an invitation to other cities attempt to create similar empires in the Aegean.

Alcibiades

These failings became obvious in the relations between Athens and her allies in the Delian League. As time went on, the other allies fell progressively under Athenian influence. All the other cities were much weaker than Athens, and it was difficult for them to resist policies that she favored. It was in the nature of the polis everywhere that Athens, once put in this position of power, would pursue policies in her own interest rather than the policies in the interests of the whole alliance. In a city-state, only the rights and interests of the citizens were considered important. Others had no rights. By the same thinking, other city-states besides your own did not have any rights either. Thus, if a city-state had the opportunity to dominate and manipulate her neighbor, she would not hesitate to do so.

Gradually, the Athenians came more and more to interfere with the activities of the Delian-League members in order to achieve her own ends. In some cases these ends were political and strategic. She tried to increase her advantage in respect to other states. In other cases, the ends were economic. Many communities that had not joined the league were attacked and forced to participate in its operations. Usually, Athens justified the attacks by saying that these cities were benefitting from the wars against Persia without contributing to them. But in some cases these cities were attacked because they were in a favorable position in the Aegean. Occasionally, a member of the league would try to withdraw from the alliance, and that member would be forced to rejoin. In some of these communities, the Athenians stationed troops and ships to prevent new disaffection in the future. In 416 B.C., Athens, with League support, invaded the island of Melos. Melos was an island that had been colonized by Sparta. The Melians resisted joining the Delian League, and the invasion as well. Athens destroyed the Melian polis, slaughtering the men and taking the women and children into slavery. Resistance was futile! You will read the “Melian Dialogue,” in which Thucydides gives the gist of the Athenians’ rationale of “might makes right.” Occasionally, Athens simply set up new governments with officials friendly to Athens. League allies were persuaded or coerced into adopting the Athenian monetary system and Athenian weights and measures so that they would find it easier to trade with Athens than with other states.

Finally, in 454 B.C., the Athenians arbitrarily moved the headquarters of the League from Delos to Athens, where, Athenians argued, it would be more secure. The League funds were stored on the Athenian Acropolis in the Temple of Athena Nike, “victorious Athena;” an ironic name that implies the victory of Athens, not over her Persian enemies, but over her own allies. Athens insisted that a part of the money collected for military purposes should be paid to Athens for guarding the treasury. With this event, the Delian League ceased to be an alliance and became instead an Athenian empire.

The ultimate results of the high-handed Athenian policy in the Delian League were first the destruction of the Athenian Empire, and in the long run, the destruction of the polis as the main form of government in Greece.

The destruction of the Athenian Empire was achieved by means of two serious wars between Athens and Sparta at the end of the 400s. These wars are known as the Peloponnesian Wars (431-421, 415-404). The Spartans usually tried to prevent the growth of powerful states in Greece as part of their traditional foreign policy. Thus, they viewed the growth of Athenian power with alarm, and that eventually led to the outbreak of hostilities. Almost every state in the Greek world was involved in the war on one side or the other.

Historians describe the Peloponnesian Wars as a match between an elephant and a whale. Sparta was the superior power on land, and Athens was the superior power on the sea, so neither side could really come to grips with the other.

Pericles was also noted for other accomplishments at Athens. He adopted policies to foster trade and commerce. He supervised most of the rebuilding of Athens after the destruction of the Persian War. He was responsible for the Parthenon and the major buildings we associate with Athens today.

The argument can be made, I think, that the ideals and goals of the Greek polis reached their highest realization in the activities of Athens in the time of Pericles. Unfortunately, however, the failings of the polis are also most evident in this period.

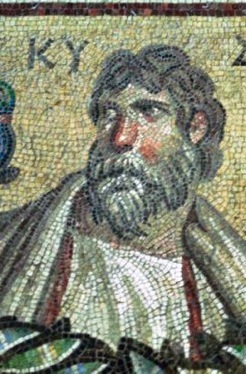

Thucydides

We know that Thucydides was born around 460 B.C., but, considering his stature as an historian and political philosopher, it is surprising that little else about his life is known. He identifies himself as an Athenian, the son of Olorus. He survived the plague at Athens that killed Pericles. He himself recorded the fact that his family owned gold mines in Thrace, and that, as a result of his familiarity with that area, he was sent as a general on the Thasos Campaign in 424. Thucydides was blamed for a Spartan victory at the Battle of Amphipolis. As a result, he was exiled from Athens. As an exile, Thucydides traveled freely throughout Greece and got an intimate view of the wars. His history ends abruptly in 411 B.C., which indicates that he may have died in that year. The historian and traveler Pausanias informs us that Thucydides was pardoned in 412, and was on his way back to Athens in 411 when he was assassinated. We don’t know if this is true or not.

Thucydides probably received an education in philosophy and rhetoric, and he approaches history through the windows of both. He warns his readers at the beginning of his history that his work will not be as entertaining as the works of previous historians (probably alluding to Herodotus) because he intends to offer the reader a rational analysis of events that will be useful to those who wish to understand the way things happen. He argues that it is important to understand the factors that cause historical events, because, given human nature, similar events will repeat themselves. He believed that the Peloponnesian War was the most important event in his time and in the history of his world. As a result, he tends to gloss over other important domestic and regional events that took place during the period. He was also acutely aware of the extent that human nature influenced events and tried to illustrate the relationship between human nature and history. Other ancient Greek and Roman historians focused on the impact that “fortune,” or long-past events had on history, but Thucydides believed that humans made their own fate by acting out their perceived interests.