The aristoi (the excellent ones) had come to consider themselves an elite class within the late Archaic polis. Well, one of the things that they thought made them excellent was their military skills. They had the spare time to drill and train in arms. They also had the disposable income to buy really good weapons and armor. They viewed themselves as “lean mean killing machines,” and they had the ability and the equipment to prove it. They also saw themselves as a class apart from the common people, so, we can assume that when they went to war they had some kind of code that required them to engage in lots of individual warfare, and primarily only with other aristoi on the other side.

We know from other cultures that when one class believes that they are superior in war to another, they adopt such codes. A couple of other examples of this kind of military culture would be the knightly culture of the European Middle Ages and the samurai culture of Japan. Part of this code also requires that individuals display what has been called “rage militaire,” that is, aristocratic warriors were impelled to fight, driven to risk life and limb, no matter what the odds. The warrior relishes opportunities to engage in battle, especially individual combat with other warriors. It is on the battlefield in individual combat with other warriors of his own class that the warrior proves himself, wins fame, prestige, honor. Remember that there were also lots of other, non-aristocratic, men on those battlefields, they are, for Homer a fairly faceless bunch who usually show up as a sum (i.e. “a thousand Myrmidons”), but to Homer and his aristocratic listeners they don’t count. It’s the melee between aristoi, the great heroes like Achilles, Ajax, Hector, Diomedes, that are important. The thousands of other nameless foot-sloggers on the battlefield are just so much window dressing.

The Art of War Changes

So much for warfare in the Homeric Age. By the end of the 700's B.C., economic and social dynamics began to change, and over the next century the Greek art of war changed with it. As I said a week or so ago, during this period poleis began to prosper, and more and more citizens were able to afford to buy the equipment that they needed to fight. Since there was already a strong assumption among Greeks that those who defended the polis should have some say in the way it was run, citizen armies grew bigger, and the aristoi became a far smaller part of the total size of the army. Gradually the aristocratic warrior became less significant, and the Greek art of war changed.

It is possible that the person responsible for the change was a tyrant and general from the city of Argos named Pheidon. Tradition suggests that Pheidon developed a new style of warfare in the mid-600's B.C. We are told that he enlarged the army of Argos, and that in 667, Pheidon used his new army to defeat the Spartans. It is possible that this tyrant invented and introduced the phalanx at that time both to defeat Argos’s enemies and to reduce the importance of the aristoi in Argos. I have to admit that this is mostly speculation, but it fits most of the circumstantial evidence that we have. So, how did this new form of warfare work?

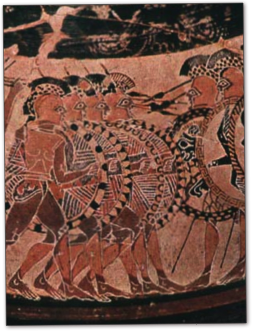

First, the new art of war depended on lots of men who dressed alike called hoplites. Each hoplite had a helmet, a breastplate, a round shield, greaves, a short thrusting sword, and a thrusting spear.

Second, the hoplites were required to act alike. The phalanx was a densely packed infantry formation that was eight men deep and as long as you could make it. Hoplites trained to advance and retreat across the battlefield in unison. Defensively, the phalanx was a row of interlocked shields. Offensively, hoplites used thrusting spears to stab their enemies. If a man in the front row was killed, he was simply replaced by the man behind him.

This new system was very successful, especially against the older melee method of warfare. In fact, it was so successful that by the end of the 7th century B.C. just about every Greek polis employed the phalanx.

For some cities, anything that endangered their phalanx endangered the polis. Sparta, for instance, as we will see, responded to a slave revolt at about this time by simply organizing its citizens into what might be called a perpetual phalanx.

The phalanx required the participation of a large citizen body. The bigger, the better. Or perhaps, more aptly, the wider, the better. The weakest parts of the phalanx were the flanks. If one side could hit the right or left flank it could roll up the whole phalanx. So if your phalanx was wider than your enemy’s you had a distinct tactical advantage.

Men had to purchase their own weapons and armor, this meant that the ability to defend your polis was based on personal wealth. But during this period Greek states had become prosperous, so there were more men who had the wealth to arm themselves and to take part in the defense of the city.

The phalanx required discipline and training. What was required in the new art of war, was not the rage militaire of the Homeric tradition. In fact, that individual code of warfare that required aristocratic heroes to run around the battlefield looking for a hero of equal fame and reputation to fight was a liability under the new system. Hoplites had to stick together. They had to move in unison to the beat of the drum or the melody of the flute, so that their wall of shields would not break as they advanced and retreated, wheeled and turned, on the battlefield. Acts of personal bravery were discouraged because each man’s shield protected not only him, but the right side of the man next to him. An act of personal bravery could break the line and lead to disaster.