By the middle of the 6th century B.C., the Persian Empire had stopped expanding. But at the end of the century, a new and very able ruler named Darius had begun to consolidate his power within the empire and use the vast resources available to him to expand his empire further. One of the areas that had already been annexed by Persia was the coast of Asia minor called ionia, which contained a number of Greek city states. The Ionian Greek city states had existed in Asia minor for several centuries. They were independent self- governing states. In the 560's B.C. these Ionian states were brought into an alliance with a larger eastern state called Lydia. The Persians conquered Lydia in 547 B.C. The Persians brought the Greek Ionian states into their empire at the same time.

The Persians had a system of government that allowed conquered peoples self-rule so long as they paid tribute to the Persian state. These Ionian cities were given self-rule and the power to make some of their own foreign policy. But the Ionians were not happy with this system and requested aid from the mainland Greeks — especially Athens. In 499 B.C. the Persians attempted to cross into Europe and expand their empire by conquering Thrace in northern Greece.

Remember that at about this time, Athens had begun to expand her own influence into the same area. Athenians traded goods for wheat in the area around the black sea. So, Persian expansion into Europe would have threatened Athenian trade and expansion into the area. What we essentially have here is competition between Persia and Athens for domination over the black sea and the western Balkans. This predisposed the Athenians to stop Persian expansion into Europe. At the same time, probably with the help of the Athenians, a great revolt broke out in all of the Ionian cities. Historians have several theories as to why the Ionians revolted at this time.

Herodotus says that the Ionian leaders gathered while the Persian armies were away and decided that the time was right to free themselves from Persian domination. While some historians have pointed out that the Persians were not particularly oppressive rulers, i should mention that the Ionians were, on at least two recent occasions, required to provide ships and sailors to the Persians without compensation for invasions of Thrace and Egypt. Some Ionian states might have found these impositions troublesome.

Some modern classical scholars suggest that the Ionian leaders had ambitions of their own in Asia Minor which they could not attain so long as they were under Persian domination. The most likely reasons are all of the above plus this: Persian domination prevented the Ionian Greeks from doing what they liked to do best — that was to fight among themselves. The revolt was successful until 494 B.C. At this time the Persians got organized and defeated the Ionians and their allies and regained control of Ionia.

The Persians began to see the mainland Greeks as a threat to them because two Greek city states (Athens and Eritrea) had come to the aid of the Ionian Greeks. In 490 the Persians sent an expedition to Greece to attack these two cities. Eritrea was defeated and destroyed, its citizens were sent to Persia and resettled.

After they finished with Eritrea the Persians sailed down the coast to attack Attica. They landed at the plain of marathon about 21 miles from Athens. The Athenians prevented the Persians from advancing by occupying the hills around marathon. The Persians couldn't advance. The Athenians spent several days debating whether or not to attack the Persians. The Persians became bored and took action. They put most of their forces on ships, probably to move up the coast and attack from another point. When the Athenians saw that the odds had improved they attacked. They defeated the Persians on land and within a few days managed to attack and destroy the Persian fleet. As a result of the Athenian victory at marathon the Persians were determined to avenge themselves not only on the Athenians, but on all of Greece.

Above: Athenian Drinking cup showing an Athenian hoplite and a Persian infantryman.

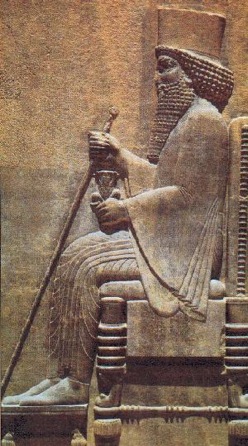

Right: Persian relief of King Darius.

Darius began to raise new troops and taxes toward a new invasion of Greece. Trouble within the Persian Empire kept him from mounting an invasion. He died in 486 and his son Xerxes took the throne. Xerxes also wanted to invade Greece, and he decided to begin his invasion on the summer of 480 B.C. Xerxes sent messengers to all of the states in Greece. The messengers commanded that the states surrender to Persian domination and send tokens of soil and hostages to Darius.

The Greeks had had ten years to prepare for the return of the Persians. What had they done in order to prepare for the invasion? Nothing! This was mainly because they had spent that ten years bickering and fighting among themselves. The Athenians had accidentally prepared themselves to meet the Persians at sea. This was because a leader named Themistocles had convinced the Athenian assembly that Athens needed a very strong navy in order to protect Athenian sea commerce, and to implement Athenian policy abroad. So from 484 to 481 B.C. Athens had enlarged the size of its navy from 50 ships to 200. Although it had been done to protect Athenian commerce, these ships would come in handy against the Persians.

After receiving Xerxes’ message the Spartans organized a congress at Corinth. Most Greek states attended, but immediately began to bicker among themselves. Even the smallest states at the conference demanded that they either share leadership of the allied army and navy with Sparta or have sole command. In fact, most Greek states submitted to Xerxes’ demands. The Athenians found that most of the other sea faring Greek states would not serve under Athenian leadership. So military leadership of both land and sea troops for the alliance was given to the Spartans. Athens agreed to provide some ships. For the most part, the forces that would defeat Xerxes in the end would be Athens and the Spartan and their Peloponnesian allies.

The Persian invasion of 480 B.C. was awesome. Persian land forces have been estimated at 80 to 120,000 men, but this estimate is probably conservative. The Persian land army was escorted by a fleet of 40-50,000 men, and lots of troop ships, transports and war ships (600 to 800 warships). Some of these ships were lost to storms early in the invasion, it is probable that only about 500 warships were left by the time they were needed for defense. The Greek states that surrendered to Xerxes provided another 200 or so ships.

The Spartans decided to establish a holding force at Thermopylae. This was a strategically located pass in central Greece. The Spartans were only able to raise a small force to defend this area though. The main reason was because Thermopylae was north of Athens, and most of the allies were from the Peloponnesus. They felt that this area was not their concern. The Spartans finally raised 7,000 men (including a small contingent of helot soldiers). They were able to hold the area for a few days. After the main force withdrew, a small force of three hundred Spartans under their king were caught in the pass and fought to the last man. This made Thermopylae famous to the Spartans.

At the same time the Persian fleet was anchored at a natural harbor called Artimision, near Thermopylai. The alliance navy attacked the Persian fleet. This sea battle was a draw. But. The Persians feared that their entire fleet would be penned in by the Greeks. Xerxes sent about 200 ships out to sea to save them from Athenian attack. These ships were destroyed in a storm. This weakened the Persian naval forces.

The Persian naval forces were enticed into the straits of salamis and defeated by the Athenian navy. The Persian fleet was demolished, but at a great cost to the Athenians. They had left Athens virtually undefended in order to concentrate all of their naval power against the Persians at salamis. The Persian army entered the city of Athens and burned the temples and public buildings on the acropolis.

The only problem was that after Salamis the Persian army had no way to get home. So they continued to move around the Greek mainland destroying crops and being a general nuisance. After Xerxes returned to Asia, he left one of his generals, Mardonios, with a force of about 75,000 Persians and some Greek allies. Mardonios continued to cause strife in Greece. Mardonios made alliances with states in central Greece and began to pressure Athens to surrender to him. The Spartan army had returned home, and had no real intention to aid Athens further. After all Mardonios offered no real threat to the Peloponnesian League, so the rest of Greece could safely be ignored for a time.

In the spring of 479, Mardonios invaded Attica, and once more re-occupied Athens. He began to systematically destroy the city. Athens told the Spartans that if the alliance wanted a navy, Sparta needed to save Athens. Sparta finally relented and came to Athens’ aid with 30,000 men. When he realized that a Spartan army was on the way, Mardonios abandoned Attica to gather more Greek allies.

The Spartans finally caught up with the Persians in 479 B.C. on a plain near the town of Plataea. The Greek army defeated the Persians soundly. This battle marks the end of Persian aggression against Greece proper.

The cities and states of Greece settled back into the patterns of the past, primarily bickering among themselves. Athenians began to rebuild their city. Spartan troops returned home. From time to time Athens and Sparta fought engagements to punish the Greek states that had surrendered to Xerxes or supported Mardonios, of had simply annoyed Athens or Sparta. For a while the Spartans tried to defend Greek states in Ionia from Persian revenge, but the Ionians decided that Spartan occupation wasn’t much better than Persian occupation. So the Ionians invited Athens to lead and defend them. This decision by the Ionian Greeks led to the creation of the Delian League which we will examine soon.