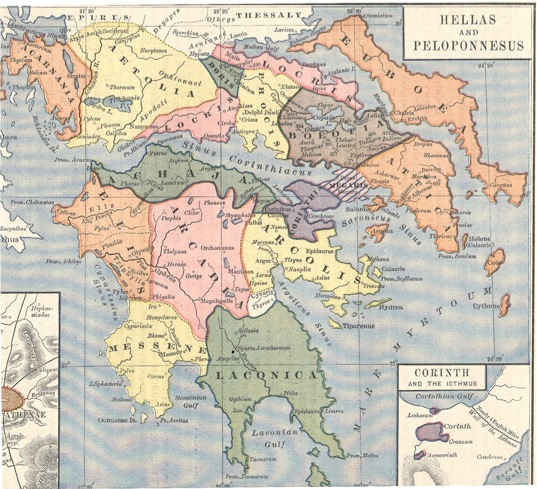

The territory of the Athenians occupied a rocky peninsula in central Greece called Attica. Unlike Laconia, the Spartan homeland, the area of Attica included very little good farmland. It was generally a poor region except for silver. The city of Athens itself was about five miles from the coast, but it was near enough to use several good harbors in her territory. This meant that if Athens were to become an important state, she would have to rely on trade rather than farming. Before 500 B.C. when Athenian trade was still limited, the polis remained backward and relatively weak. But as her trade developed after 500, she became one of the most powerful and most progressive of all the Greek city-states.

The dialect of Attica is closely related to the Ionian (Iconic) dialects. This means that the original population of Attica were predominately Mycenaean Greeks who lived in Attica before the start of the Iron Age.

Evidence about the earliest organization of the Athenian polis is limited, but there is enough information to give at least some idea of the conditions there. As I suggested above, Athens remained relatively backward during her early history. This is reflected in her constitution, which remained an aristocracy dominated by a few families as late as 600 B.C. In the executive branch of government the basileus was replaced by a board or committee of nine officials called archons The archons were elected each year. Each official was responsible for some aspect of the administration – war, religion, justice, etc. The council at Athens in the earliest period had considerable powers. The council was made up of former archons. After their year as archon was over, the officials became permanent members of the council. There was an assembly which elected officials and made important decisions, but it could take action only on those matters that the council placed before it.

Participation in this early government was limited in two ways. Like Sparta, Athens had expanded in the years before 600, taking into its system many outlying farms and villages. The people who were annexed in this fashion were not citizens. They had no role in government at all. Even in the citizen-body itself there were restrictions. All citizens could vote in the assembly, but only members of certain families could hold the archonship.

These families were called eupatridae, nobly born. They dominated politics by holding the archonship and controlling the council. This system was extremely unstable because of the bad economic conditions in Attica. Before 600 most persons in the region were still farmers, and the limited farmland made it difficult for these persons to make a living.

Between 750 and 600, the population of Attica gradually increased. As it did, it became increasingly more difficult for farmers to produce enough food to feed the whole family. In bad years, these small farms would have to borrow food from their richer neighbors, the eupatridae, who might have some left over. Once a farmer fell into debt, it was hard for him to pay off, for he now had to produce enough to feed his family and also enough to pay back what he had borrowed. By 600, many persons – perhaps most of them– had become permanent debtors. They merely paid a fixed sum to a wealthy neighbor with no hope of completely clearing the debt. Worse yet, they were sometimes cheated by their creditors, who might charge high and unreasonable interest.

As conditions worsened, the farmers appealed to the government for help, but the government was unwilling to do anything. The government was controlled by the eupatrid families, and the eupatrids were the men from whom the money was borrowed. Even if he had been cheated, the farmer usually could not get satisfaction because the man who cheated him was likely to be a cousin of the judge.

This then was the condition of Athens in 600 B.C. We saw earlier that Sparta also had an oppressive system and that the Spartan system never changed. In Athens, the economic conditions were so bad that change was necessary. Between 600 B.C. and 500 B.C., events occurred that completely remade the Athenian state.

Reform under Solon

The reform began in 594 B.C. when the danger of revolution became so great that the eupatrids agreed to allow reform. They appointed a man archon, for one year with the power to introduce whatever changes he wished. The man chosen for this was named Solon. He was a eupatrid himself, but he placed the interests of the city above those of the aristocracy to which he belonged. He reformed the basis of participation in government by allowing any persons with wealth to hold the archonship and sit on the council. In this way, he converted the city from an aristocracy with an oligarchy. Office holding was now dependent on wealth, not birth. This may not seem an improvement, but it was. Now any citizen could become archon provided he made a lot of money first. As a related reform, Solon gave citizenship to some people who were not citizens before.

A second notable reform of Solon was to publish the laws of the polis. Before this time, there was no written law. The archons merely kept the law in their heads, so that they could change the interpretation of it whenever they wanted. Solon put the laws on tablets in the city. After Solon’s time, the laws were available for anyone who wanted to read them. This ended irregular justice. Finally, Solon attacked the problem of debt by merely abolishing all the debts outstanding in his time.

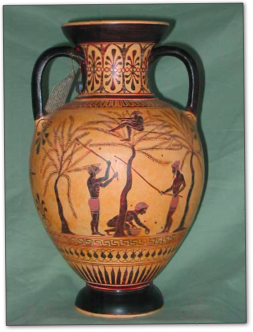

Solon also created laws that made it illegal to export grain. These agricultural laws were very important. Since it was illegal to export grain, eupatrid farmers were encouraged to find some other crop to export. The best crop for the export market was olives. But, it takes over twenty years to produce olive oil from scratch. You have to plant trees that take two decades to mature. You also have to invest in oil mills. This change in Athenian crop production was only a logical choice for wealthy farmers. It had the effect of setting back Athenian aristocrats by two decades.

Peisistratos’ Tyranny

The main failing of Solon’s program was in the debt abolition. He had ended the debt, but he had done nothing to prevent new debts in the future. After about fifty years, the situation was right back where it started. This led to the establishment of a tyranny at Athens (549-10). You may remember that a tyrant was an illegal ruler who would seize control of the government of a city in times of unrest. In Athens the tyrant was a man named Peisistratos, who gained the support of the small farmers for his rule. He was absolute leader from 549-517, when he died. He made all the decisions and dominated the other organs of government. After his death, the position of tyrant was taken by his son Hippias, who continued to rule until 510.

The tyrants did nothing to alter Athenian government, but they carried out many reforms to improve the economic system. Peisistratos reformed the money system in a way that promoted the growth of trade and commerce. He took other steps to encourage trade. He created many new religious ceremonies to attract visitors and tourist money to the city. And he built many new temples to provide jobs for those who could not make a living as farmers. These actions effectively relieved the economic pressures on Athens. By making Athens a commercial city rather than an agricultural one, Peisistratos provided alternative jobs for depressed farmers. He also further reduced the power of the Athenian aristocrats whose power base was rural rather than urban. By increasing the political power of those who lived in the city and took part in merchant activities, Peisistratos both reduced the power of the eupatridae and also changed the focus of Athenian politics. This policy was disastrous for the tyranny. Once economic unrest was alleviated, no one wanted a tyrant any more. Thus, in 510, Hippias was driven out and legal government restored.

Reforms of Cleisthenes

The end of the tyranny paved the way for new changes in the government itself. The economic policies of Peisistratos had greatly strengthened the craftsmen and merchants of Athens, who were unhappy with the older system of oligarchy. Two years after the end of tyranny in 508, a reformer named Cleisthenes pushed a reform of the government through the assembly.

Cleisthenes eliminated the four traditional tribes, which were based on family relations and also gave more power to rural citizens, and organized citizens into ten tribes according to their area of residence (their deme). He also established legislative bodies run by individuals chosen by lot, rather than kinship or heredity.

Although evidence is uncertain, Cleisthenes apparently got a bill extending citizenship to most of the free inhabitants of Attica who were not already citizens (called metics). Metics were non-Athenians who had moved to Athens to take part in the trade and mercantile activities of the city. Their interests were primarily urban rather than rural. So, their participation in Athenian government was more focused on city activity than rural, which further diluted the influence of the country aristocrats. He lowered the property requirements for holding the archonship so that all but the very poorest citizens were eligible to serve. But the most important reforms had to do with the way the Assembly conducted its business. The old council of archons was deprived of its power to arrange business of the assembly. In its place a new council was created called the Council of 500.

The Council of 500 was made up of 500 men chosen annually by lot. They were not elected, and the membership changed each year. The lots were drawn in a way that the council would represent a cross-section of the whole demos. This was an important reform because it made the assembly essentially an independent body. They assembly could not only make decisions but also decide what questions required debate. In essence, the Athenian assembly became a real deliberative legislative body under Cleisthenes, and since it was made up of a fairly broad range of Athenian citizens, Athens became pretty democratic.

The reforms of Cleisthenes essentially changed the government at Athens from an oligarchy to a democracy for the first time. Once democracy was established, Athens began to progress very rapidly as a result of her developing commerce. Between 500 and 479 B.C., Athens emerged as a major power in the Greek world, and we need to consider this development now.

Themistocles and Athenian Sea Power

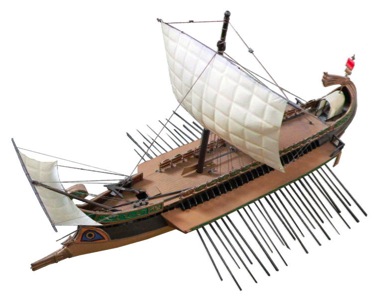

The man responsible for the growth of Athenian power was named Themistocles. He was the major Athenian leader from the 480s to 471, and he perceived that it was necessary to have a strong navy if trade was to become strong. Under his leadership, the Athenians built a navy of 200 ships, which was by far the largest fleet in the Greek world.

This Athenian fleet proved to be a decisive factor in a series of terrible wars that broke out after 500 between the Greek cities and the newly formed Persian Empire. Now you should remember that the Persians began expanding around 550 B.C. and that they succeeded in conquering most of the Near East.

One group of states that fell under Persian control were the Ionia Greek cities on the coast of Asia Minor. The Ionians resented the Persian control, and they led an unsuccessful revolt against Persia from 499-493.

A Greek trireme. It was these warships that Themistocles decided that Athens needed -- a maritime “wall of wood.”