Ethics Among the Classical Greeks

Ethics Among the Classical Greeks

The earliest Greek philosophers, the pre-Socratics, were not particularly interested in how men should act or govern themselves. They did not need to be. In the late sixth and fifth centuries B.C., Greeks assumed that the polis was the perfect form of government and that the laws and traditions of the polis would tell them how to act. As we have seen, a few questions of human action were not covered by the rules of the polis, but until the very late 400s, these questions were taken up, at least at Athens, by the tragic playwrights rather than by philosophers. Philosophers and other Greek thinkers began to question these assumptions after 450 B.C., during the time of the Athenian Empire and the Peloponnesian Wars, when Greeks began to question whether the polis was the perfect arbiter of human behavior that they had assumed.

Some of the first thinkers to question the values of the polis were the Sophists. The profession of Sophist arose because many Greek cities became democracies in the 400s B.C. In order to have influence in a democratic polis, a man had to be able to speak persuasively in the assembly. That created a demand for people who could teach would-be politicians how to speak and argue in public. The Sophists were professional teachers of rhetoric or speech-making.

But Sophists did not merely teach men how to speak. They also trained them to make wise political decisions. Sophists criticized traditional ideas about how men should act. Greeks had always thought that a wise political decision had to be moral, in keeping with traditional ideas of right, because the gods would punish cities that acted immorally. But the Sophists argued that most successful political decisions are not moral, but practical. The only way to judge them was to see whether they accomplished what was intended. If a leader persuaded a city to go to war and the city won, it was a wise decision; if the city lost, it had been a very unwise decision. We might call this situational ethics. A good decision is one that gets the politician what the members of the demos think that they need. It is a good decision from the point of the politician because it keeps him in power. That is all you can know about it. For Sophists there is no absolute standard that enables humans to judge right and wrong beyond the sweet smell of success.

The Sophists argued that you cannot know what the gods want because human customs and governments are not created by the gods or by the laws of nature. But if that is true, where do they come from? One famous Sophist, Protagoras of Abdera (d. 415) answered this question by saying: “Man is the measure of all things.” That is, it is men who create all human institutions, customs, and beliefs. Right and wrong are simply a matter of what people believe at any given time in any given place. Morality is simply a matter of opinion.

The Sophists argued that there is no true morality, only opinions about right and wrong that can change. This idea troubled one fellow, an Athenian sculptor named Socrates (d. 399 B.C.). Socrates thought that the Sophists were wrong. He believed it was possible to have an absolute standard of right and wrong. But that standard had to be logical and based on a logical understanding of the world. He agreed that many earlier Greek beliefs about government and morality were incorrect because they were not logical.

Socrates set out to show that many Greek beliefs, including those of the Sophists, were illogical and incorrect. He went around Athens starting conversations with people. He would ask them to say what they believed about something — government, morality, religion, etc., then he would ask them questions about what they said, forcing them to explain and justify their answers until he could show that what they had said was illogical and false. In this way, he proved to individuals that what they had strongly believed was not true at all. In other words, Socrates was an obnoxious fellow who spent the better part of forty years showing most Athenians that they were illogical, cretinous, and just plain wrong. Unremarkably, after four decades of this kind of activity, Socrates had become so unpopular that, in 399, he was tried for sacrilege and corrupting the youth of the city, and executed.

Socrates demonstrated that philosophers could use reason and logic to show that people’s beliefs about morality and government were not true. Later philosophers used them to show what was true. Several of Socrates’ students tried to redefine the nature of the Good Life after the death of their mentor.

One school that we call Cyrenaic Hedonism, was founded by Aristippus, a pupil of Socrates. Aristippus taught that the ultimate goal of all our actions is pleasure (hêdonê), and that we should not defer pleasures that are ready at hand for the sake of future pleasures. He and his Cyrenaics supported immediate gratification. Even fleeting desires should be indulged, for fear the opportunity should be forever lost. At least in part, Aristippus’ notion that pleasures should be experienced as the opportunity presents itself, has something to do with his theory of sensation. Aristippus argued that:

Sensations are entirely individual and can in no way be described as constituting absolute objective knowledge.

Sensations are entirely individual and can in no way be described as constituting absolute objective knowledge.

Sensory experience is rooted in the moment of sensation. Past and future pleasures have no real existence for us. To quote an oft used phrase from the ‘60s, “its what’s happenin’ now, man!”

Sensory experience is rooted in the moment of sensation. Past and future pleasures have no real existence for us. To quote an oft used phrase from the ‘60s, “its what’s happenin’ now, man!”

Feeling, that is sensory input, is the only trustworthy basis of knowledge or conduct. Intellectual knowledge, reason and science are all suspect. Feeling, therefore, is the only possible criterion alike of knowledge and of conduct.

Feeling, that is sensory input, is the only trustworthy basis of knowledge or conduct. Intellectual knowledge, reason and science are all suspect. Feeling, therefore, is the only possible criterion alike of knowledge and of conduct.

Personal existence is to be found in the present moment, as well. Aristippus observed that a person’s age brings on change. I am not the same person that I was 25 years ago, and I will not be the same person in 25 years that I am now.

Personal existence is to be found in the present moment, as well. Aristippus observed that a person’s age brings on change. I am not the same person that I was 25 years ago, and I will not be the same person in 25 years that I am now.

These ideas allow for some rather profound conclusions:

Many ethical thinkers have warned us that today’s pleasures may cause tomorrow’s pain; that we should not engage in experiences in the present that may carry dire future consequences. Some pleasurable activities may cause damage to our health — cancer, STDs, whatever. Similarly, we should not pursue pleasures today that are so expensive that they will beggar us in our old age. We should not do things that society finds so reprehensible that it will eventually punish us for our pleasures. Cyrenaics would argue that the recipients of the consequences mentioned above will be our future selves who are essentially “some other guy.” Why should I care about what will happen to some person that isn’t me?

Many ethical thinkers have warned us that today’s pleasures may cause tomorrow’s pain; that we should not engage in experiences in the present that may carry dire future consequences. Some pleasurable activities may cause damage to our health — cancer, STDs, whatever. Similarly, we should not pursue pleasures today that are so expensive that they will beggar us in our old age. We should not do things that society finds so reprehensible that it will eventually punish us for our pleasures. Cyrenaics would argue that the recipients of the consequences mentioned above will be our future selves who are essentially “some other guy.” Why should I care about what will happen to some person that isn’t me?

Since only sensory experience is trustworthy and since our knowledge and reason is untrustworthy, then no moral or ethical philosophy can offer us a worthwhile alternative philosophy to replace “eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow we will die.”

Since only sensory experience is trustworthy and since our knowledge and reason is untrustworthy, then no moral or ethical philosophy can offer us a worthwhile alternative philosophy to replace “eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow we will die.”

Thus, we should have no goal beyond present sensual fulfillment. There was little to no concern with the future. Cyrenaic hedonism encouraged the pursuit of enjoyment and indulgence without hesitation. Pleasure becomes the only good.

Thus, we should have no goal beyond present sensual fulfillment. There was little to no concern with the future. Cyrenaic hedonism encouraged the pursuit of enjoyment and indulgence without hesitation. Pleasure becomes the only good.

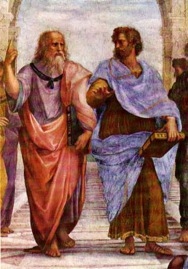

Another of Socrates’ students, and his most famous, Plato (d. 347), created a logical theory of the world that could serve as the basis for correct moral decisions and behavior. Plato’s view of the world is called the Theory of Ideas. He argued that everything in the world is what it is because of its form. The form is defined by a perfectly logical idea of the thing.

Plato said that these definitions or ideas are real things that exist in a separate world of their own. The World of Ideas is a perfect blueprint of our world, the world of nature. Plato’s concern for morality influenced his view of these two worlds. If something is to be morally true, it must always be true in every situation. Morality and moral ideas cannot change. In our world, things do change. If we cut the legs and back off a chair, it is not a true chair anymore. But the definition or idea of a chair never changes; it is always true. Thus, Plato argued that the perfect World of Ideas is true and real. Our world, the world of nature, is imperfect. The things in it are not true things and so are not completely real. Plato would argue that we learn about things by thinking about them, not by experimenting on them. He believed that when men understood the world of ideas logically, they would automatically act in logical, moral ways. They would also be able to create more logical, moral governments and customs.

After Plato died, one of his students, Aristotle (d. 322) created a new theory of his own that used some of Plato’s conceptions but differed from his theory in major respects. Aristotle accepted the notion that everything is what it is because of its form, but he worried about the view that the forms were determined by a static, unchanging blueprint like the World of Ideas.

If forms were static definitions, they could not change. But Aristotle was interested in natural philosophy (the grandfather of natural science, if you will), especially biology, and he knew that some animals change in form. For example, caterpillars change into butterflies in later life. This happens naturally. Aristotle wanted to explain such changes. He argued that there is no separate, unchanging design for the world. Instead, there is an intelligent, active plan that makes everything in the world and also makes it change. Everything in the world has a telos or, as we would say, a purpose to fulfill. The purpose of a thing determines its form, and when its form changes by regular, natural stages, it changes to fulfill the purpose set for it in the plan. Aristotle does not mean accidental or incidental changes that occur within all animals or things of the same type. He believed that developmental changes occur not only in animals, but also in such things as moral behavior and government. He considered proper human conduct as a separate field of study like any other. Being good consisted of applying certain logical principles of good behavior to particular situations.

Aristotle believed that ethical knowledge is not precise knowledge, like logic and mathematics. He stressed that ethics is a practical discipline rather than a theoretical one. To become "good", one could not simply study what virtue is; one must actually be virtuous; virtue requires practice. Like an athlete who strives for excellence, one must not only study the theory of the sport, but get out and do it, a lot! Aristotle argued that everything was done with some goal in mind, and, in the case of ethics, that goal is to do “good.” The ultimate goal he called the Highest Good (eudaimonia) which could be translated as “happiness,” or perhaps more succinctly as “living well.” In other words, for Aristotle, to achieve the Good Life, we must determine what is ethical behavior, then strive to act well in order to achieve the goal of living well. When our behavior meets the criteria for the Good Life, we have arrived.