Individual, Oikos & Polis

Individual, Oikos & Polis

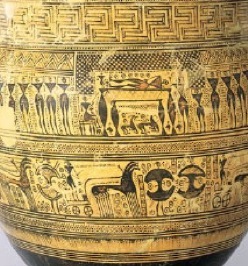

In this unit we will examine the development of Greek social thought from the Greek Dark Age (c. 1150-750 B.C.) into the Greek Classical Period (begins c. 480 B.C.). A high level of civilization existed in Bronze Age Greece called the Mycenaean civilization. The Mycenaean culture disappeared from Greece around 1200 B.C. The end of the Mycenaean period marked the end of any high civilization on the Greek mainland for about 350 years. This period is referred to as the Greek Dark Ages. Greece became isolated from the rest of the eastern Mediterranean and Greek society reverted to a very primitive state.

The Greek Dark Age

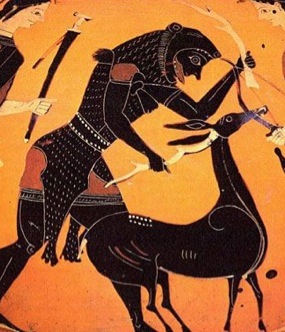

In the Mycenaean period there had been a dominant, and very clearly defined, ruling class. During the Dark Age these older class distinctions largely disappeared, primarily because there simply wasn’t enough material wealth for an elite class to exist. City states on the Mycenaean model gave way to small communities, often founded on the ruins of the Mycenaean citadels, and small family groups tied to specific, relatively small tracts of land. The basic unit of government and society was the oikos, which might best be translated as “household.” Each household had its own religious observances, laws and loyalties. Members of the oikos included the central extended family, landless warriors who threw in with the family, retainers who were technically free, and farmed and tended livestock, and finally a very few slaves who had been taken in battle. Small communities that grew up on the ruins of Mycenaean sites were often organized along primitive lines.

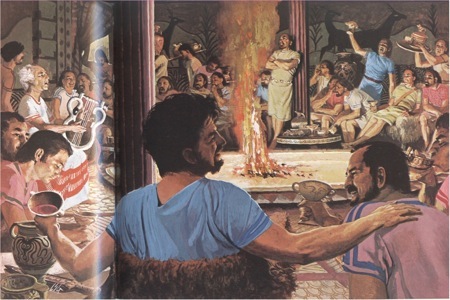

The aristocrats became a distinct and elite class within the polis. The aristocrats had more leisure time and more wealth. Which they used to take greater advantage of the fruits of trade with the outside world. They associated with each other. They engaged in intellectual activities such as listening to poets, and discussions about epics, philosophy and warfare, and improving their military skills.

The aristoi developed a “class consciousness.” that is, they began to see themselves as a group set apart from, and superior to, other citizens, not because of their wealth, but because of some special quality which they alone had. They developed family trees which emphasized that their family had been founded by some mythical hero or god. They told stories that emphasized their importance and power, and they controlled their communities.

But, aristocratic control over many Greek communities was fairly short lived. The strong presumption of equality, and changes in the economic and social structures within the polis, made it impossible for any one class within the community to exercise complete control. But, how to get rid of, or at least control, the aristocrats, that’s the problem! The answer for the Greeks was the creation of a new kind of ruler called a tyrant.

The high-handed manner in which the aristoi treated the people caused a great deal of discontent among the lower classes. Some members of the aristocratic class began to support reform. But since the aristoi had a stranglehold on the government of the polis, it was difficult to use the traditional means of legislation to pass reform laws.

So the individuals promised reform and used violent means to gain control of the state. In this way the rule by an aristocracy was replaced by rule by a tyrant. Tyrants usually were themselves members of the aristocracy who used the broad power base of popular support to defeat their fellow aristoi and gain personal power. Although tyrants gained control of the polis in order to pass reforms, they occasionally became brutal and absolute as time went on. The new form of government would vary. In most cases the new government would be more democratic. The trick was to figure out ways to dilute the power of the aristoi.

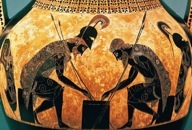

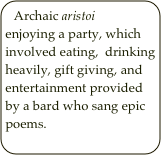

One way was to change the traditional approach to warfare. The aristoi were a warrior class that excelled in individual combat. Early Archaic warfare consisted of melees in which aristocratic warriors fought mano a mano with their equals to achieve glory and loot. In the late 600s B.C., a new style of warfare was introduced that employed the phalanx. The new art of war depended on lots of men who dressed alike called hoplites. Each hoplite had a helmet, a breastplate, a round shield, greaves, a short thrusting sword, and a thrusting spear. The hoplites were also required to act alike. The phalanx was a densely packed infantry formation that was eight men deep and as long as you could make it. Defensively, the phalanx was a row of interlocked shields. Offensively, hoplites used thrusting spears to stab their enemies. If a man in the front row was killed, he was simply replaced by the man behind him. The tactics of the phalanx discouraged individual melees and emphasized the integrity of the formation. It replaced warriors with soldiers and made every male citizen an equal. The phalanx became by 500 B.C., the standard Greek unit of warfare.

One way was to change the traditional approach to warfare. The aristoi were a warrior class that excelled in individual combat. Early Archaic warfare consisted of melees in which aristocratic warriors fought mano a mano with their equals to achieve glory and loot. In the late 600s B.C., a new style of warfare was introduced that employed the phalanx. The new art of war depended on lots of men who dressed alike called hoplites. Each hoplite had a helmet, a breastplate, a round shield, greaves, a short thrusting sword, and a thrusting spear. The hoplites were also required to act alike. The phalanx was a densely packed infantry formation that was eight men deep and as long as you could make it. Defensively, the phalanx was a row of interlocked shields. Offensively, hoplites used thrusting spears to stab their enemies. If a man in the front row was killed, he was simply replaced by the man behind him. The tactics of the phalanx discouraged individual melees and emphasized the integrity of the formation. It replaced warriors with soldiers and made every male citizen an equal. The phalanx became by 500 B.C., the standard Greek unit of warfare.

Tyrants in other cities, especially Athens and Corinth, introduced reforms that encouraged trade and commercial activity and stimulated tourism. These reforms enriched the polis center at the expense of agriculture, the mainstay of the aristoi. Polis headquarters grew into urban centers with growing and increasingly wealthy urban citizen populations. The wealthy commercial class came to outnumber the aristocrats and wield more political power as a result of their numbers and wealth.

Tyrants in other cities, especially Athens and Corinth, introduced reforms that encouraged trade and commercial activity and stimulated tourism. These reforms enriched the polis center at the expense of agriculture, the mainstay of the aristoi. Polis headquarters grew into urban centers with growing and increasingly wealthy urban citizen populations. The wealthy commercial class came to outnumber the aristocrats and wield more political power as a result of their numbers and wealth.

Tyrants introduced democratic reforms that gave greater voice to citizens who served on the phalanx. Increasing democracy and an increasing number of involved citizens diluted the political influence of the aristoi.

Tyrants introduced democratic reforms that gave greater voice to citizens who served on the phalanx. Increasing democracy and an increasing number of involved citizens diluted the political influence of the aristoi.

The Spartan tyrant, Lycurgos reformed Sparta into a military state in which all citizens were equal in social and political status and even, to some extent, wealth.

The Spartan tyrant, Lycurgos reformed Sparta into a military state in which all citizens were equal in social and political status and even, to some extent, wealth.

In the process of weakening the power and hold that the aristoi over the city states of Greece, the tyrants increased the power and influence of the state, the polis, over its citizens. By the end of the 500s, the polis, rather than the family or the aristocratic individual, had become the arbiter of social values. Classical Greek civilization emerged as the glorification of the polis. It became ill-mannered, improper, and just plain unGreek to differ in conspicuous ways from one’s fellow citizens. As a result, the monuments of Greek civilization are not palaces of kings but temples to the gods, amphitheaters in which all of the citizens might meet, and works of art that glorified, not so much individuals, but one’s home city. Aristotle wrote that, “We must not regard the citizen as belonging to himself; we must rather regard every citizen as belonging to the state.”

Probably the first Greek community to benefit from renewed prosperity and trade was Athens. This Bronze Age Mycenaean community had been less adversely affected than other areas by the fall of Bronze Age civilization, so it was most likely the first area to revive. Artifacts found at Athens indicate that the economy had weathered the Dark Age and prospered throughout the period.

Eventually more formal political institutions emerged in some cities of Greece. By the late 800's B.C. limited trade was restored between Greece and the Near East. From this contact, and from the information about the Mycenaean Age left to them in their epics, some Greek cities began to develop more complex structures of government. The growth of prosperity contributed to growth of government. A food surplus in the late dark ages caused a rise in population, which in turn led to a need for greater organization. Family and tribal government was not enough. Towns arose in Greece, and these communities required some way to settle disputes peacefully, and to represent themselves in extra-community activities. The communities began to absorb all of the functions of the oikos, becoming a sort of super-family. This is important because it means that there was a strong assumption in these early Greek communities that everyone who bore arms in the defense of the community was equal.

This is the basis of the Greek polis. “Polis” could be defined as city, or city-state, or community. In fact, the polis was a sort of community headquarters. Most members of the community lived outside of the polis on small farms. They came to the polis only when it was necessary for the community to meet as a whole. A state dominated by a particular polis would never become very large though, because was hemmed in by natural barriers such as the sea or mountains.

As the polis developed political power shifted from the family and tribal chieftains to a single hereditary king (basileus) who had both political and religious duties. But the king of a polis was never as strong as an Eastern monarch or a pharaoh. There were a couple of reasons for this:

There was no precedent for a strong central ruler in Greek tradition. Families and villages had had a war leader or “Big Man,”, but day-to-day decisions had been made by the council of elders (called the boule).

There was no precedent for a strong central ruler in Greek tradition. Families and villages had had a war leader or “Big Man,”, but day-to-day decisions had been made by the council of elders (called the boule).

Even though the basileus was king he was still a member of the polis. And therefore, despite his duties and political position, he was no more important than any other citizen.

Even though the basileus was king he was still a member of the polis. And therefore, despite his duties and political position, he was no more important than any other citizen.

Leadership skills were still linked to battle skills. So, a stronger or more able warrior might come along and challenge and replace the basileus. This would make it difficult to enforce continuity in leadership.

Leadership skills were still linked to battle skills. So, a stronger or more able warrior might come along and challenge and replace the basileus. This would make it difficult to enforce continuity in leadership.

The solution was for the community to elect an annual magistrate to represent them in political and religious matters and to provide a check on the king. The position carried no pay and required a lot of time. Only a wealthy individual could afford to hold office. Gradually the magistrate came to replace the basileus altogether. When the king was replaced by a magistrate, the council, became a deliberative organ of government. The boule met and determined policy for the community. In this way the boule became very influential.

At about this time the citizens, that is, all of the males who bore arms in defense of the community, began to meet in order to vote on issues that were important to the entire population of the polis. The assembly of citizen warriors had no power to make proposals. This power was held by the boule. The assembly could only vote yes or no on the proposals handed down to them by the boule.

As you can probably guess, the boule gradually became the most important group in the polis. It came to contain the most important citizens, the “best” men of the community — the aristoi. These men were the members of the community who were the largest landholders. These men gradually came to rule the archaic polis. Aristocratic rule became a feature of greek politics in the period.

Now, I just said that there was a strong presupposition of equality in Greek communities. So, how did aristocratic families come into existence? In the late Dark Ages prowess in war was considered the most excellent quality that men could have (arete). Some men gained great prestige through military accomplishments. These men were called aristoi (excellent ones). Since the best soldiers tended to obtain more loot, their families became richer than the other families. They got the largest share of any new lands. Since the aristoi had the largest land holdings, they had surplus wealth to lend to the other farmers. If the farmers who borrowed from the aristoi were unable to repay the loans, the lender might either take the borrower's land, or the borrower might be forced into slavery until the debt was paid. Thus the aristoi became even wealthier. These same wealthy families came to have great political power. Their wealth gave them leisure time which was necessary in order to hold the political positions of the polis, as magistrates and council members, they controlled the policies of the polis.

An additional factor that aided the growth of Early Archaic Greek communities was a realization of relatedness among the various oikoi in some valleys of Greece. Years of wife stealing and carefully arranged marriages had contributed to the biological fact that folks in nearby oikoi were cousins. But how to solve the problem of long-held grudges and blood feuds? The solution lay in the creation of regional heroes, the growth and promotion of the idea that genoi (related clans) were united by a common important ancestor who happened to be a hero. A hero was often a semi-divine shared ancestor who was long dead. The cult of the shared hero progenitor formed the center of the community, a community comprised of families that had previously been unable to live together in peace. The hero cult united all of the families into a familial and spiritual whole. Each family had an altar to the hero in their homes or on their lands, and a larger altar or building was devoted to the cult to be used by the entire genos on special feast days and other occasions.

Heracles was one of the best known and most important of the Archaic heroes, with cults set up to him all over the Aegean.

Greece in the Dark Age might best be described as a frontier society. Folks protected what was theirs and occasionally took what they could from other oikoi. Inter-familial or inter-community activities were most often those of the blood feud. Because there were virtually no differences of wealth within the family, there existed a strong assumption the all males old enough to fight were equal. Often, thus, the major decisions of oikos or community were made by the head man after consultation with the other elder men within the social unit. But, individual leader held the most power, and wielded the strongest say in all matters.

Our first reading in this unit, The World of Odysseus by Moses Finley, will yield important insights into the social and political structure of the Greeks during this period. Pay a lot of attention to the important cultural components of the age, and the extent to which these components helped to create the ideas that were inherent in the Greek archetype of the hero. You might also go back to the page within this website that covers ideas about heroes for a refresher.

Archaic Greece

Over time, small villages began to develop. These villages became the centers of local government, of markets and for craftsmen to produce and market their wares. In the mid-800s B.C., Greek agricultural production began to increase and populations began to rise. As prosperity began to return to Greece, some villages began to grow into larger towns and trade all over the Eastern Mediterranean grew, encouraging further town growth and better organized government and economic activity in the Greek world.

Government of the oikos or primitive community was relatively simple. The family acted to protect its members from outsiders, and male family members combined both to defend their own family, lands and livestock, and, from time to time, to raid neighbors and steal livestock and women. Decisions affecting the whole oikos were made by a council of elders, probably under the guidance and influence of the family head. The pattern of community government was based on the idea of the “Big Man,” a semi-formal leader whose primacy is based on his ability to rule and to maintain his position through gifts, good decisions and his own physical prowess. The family head and the “Big Men” probably form the basis for ideas about heroes.

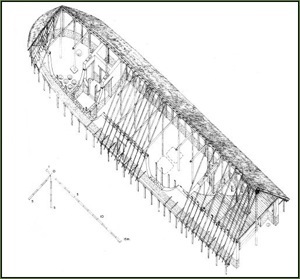

A family dwelling at Lefkandi, a Dark Age site in central Greece. Note it is a wooden structure with only one way in or out.