After the defeat of their army in 479, the Persians withdrew their forces from the mainland of Greece, but that did not mean that the threat from Persia was ended completely. Persia still controlled the Ionian Greek cities on the coast of Asia Minor just across the Aegean. In this position, it was always possible that they might mount a new invasion of Greece at any time.

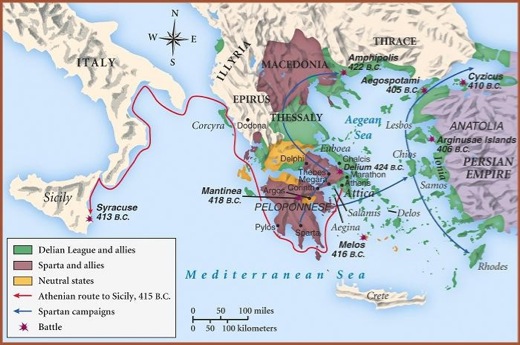

For this reason, a number of Greek states decided to set up an alliance to continue the war until Persian influence had been eliminated from the Aegean area entirely. In the winter of 478/477, they agreed to set up a new defensive league for the purpose of prosecuting the war. The participating cities were mainly from the Aegean islands and the northern parts of Greece. Because Sparta did not want to involve her armies in such long-range operations, she and the other members of the Peloponnesian League did not belong.

The headquarters of the league was established on the island of Delos in the center of the Aegean. For that reason, the alliance was know as the Delian League. The league was a military assistance pact similar to NATO. Each member of the alliance was required to contribute to the military effort according to its means. Large cities gave ships and men for the forces. Smaller cities merely gave money to finance operations. The league members were to meet each year to decide on the strategy for the year to come. Each city had one vote. Since Athens had the largest fleet, she was selected to lead the forces of the League. She supervised the collection of the money, and she furnished the commanders for military operations.

This alliance was extremely successful in its efforts against Persia. By 450 B.C., all of the Ionian cities of Asia Minor had been freed from Persian domination. Persian influence was eliminated. As the Greeks of Asia Minor became free, they too joined the Delian League so that the influence of the alliance gradually grew. And, of course, the influence of Athens, as the leader of the alliance, also grew whenever the league expanded.

The growth of Athenian power in foreign policy was accompanied by a great advance in the internal organization and prosperity of the polis as well. The man most responsible for this progress was Pericles.

The major accomplishment of Pericles internally was the perfection of the Athenian system of democratic government. This system had continued to grow more democratic since the time of Cleisthenes in 508; now it was completed. At some point, probably during the time of Themistocles, the archons, who were the major officers of the state, ceased to be elected. Instead, they were chosen strictly by lot. There was a drawing, and the men whose names came up were archons. Thereafter the only officials who continued to be elected were a committee of ten generals, who led the armies. The generals had to be elected because their jobs were too technical to be left to chance.

Pericles was responsible for two measures which extended democracy even further. First, he eliminated the last property requirements for holding office. Now, any Athenian could be archon if his name came up. Second, he introduced the practice of paying any person who served in public office. This was important because previously, no one received pay for any public service. This meant that poorer citizens often had to work during the assembly meetings. Now they could all go.

This system was a perfect democracy because every citizen could hope to hold office and to influence the making of policy. If a man was dissatisfied with the way the government was run, all he had to do was got to the next assembly meeting and say so. If enough other citizens agreed with him, they could vote to change things. This meant that a man would could speak well and persuasively in the assembly often had great influence in policy even if he did not hold any public office proper. Such men were called demagogues, which means leader of the demos. Remember that demagogue is not an office. Frequently demagogues were so popular that they might hold the elective office of general. This is how Pericles could be a major leader for thirty years. Many but not all of those years he was general.

Pericles was also noted for other accomplishments at Athens. He adopted policies to foster trade and commerce. He supervised most of the rebuilding of Athens after the destruction of the Persian War. He was responsible fo the Parthenon and the major buildings we associate with Athens today.

The argument can be made, I think, that the ideals and goals of the Greek polis reached their highest realization in the activities of Athens in the time of Pericles. Unfortunately, however, the failings of the polis are also most evident in this period.

These failings became obvious in the relations between Athens and her allies in the Delian League. As time went on, the other allies fell progressively under Athenian influence. All the other cities were much weaker than Athens, and it was difficult for them to resist policies that she favored. It was in the nature of the polis everywhere that Athens, once put in this position of power, would pursue policies in her own interest rather than the policies in the interests of the whole alliance. In a city-state, only the rights and interests of the citizens were considered important. Others had no rights. By the same thinking, other city-states besides your own did not have any rights either. Thus, if a city-state had the opportunity to dominate and manipulate her neighbor, she would not hesitate to do so.

Gradually therefore, the Athenians came more and more to interfere with the activities of the Delian-League members in order to achieve her own ends. In some cases these ends were political and strategic. She tried to increase her advantage in respect to other states. In other cases, the ends were economic. Many communities which had not joined the league were attacked and forced to participate in its operations. Usually Athens justified the attacks by saying that these cities were benefitting from the wars against Persia without contributing to them. But in some cases these cities were attacked because they were in a favorable position in the Athenian world. Occasionally, a member of the league would try to withdraw from the alliance, and that member would be forced to rejoin. In some of these communities, the Athenians stationed troops and ships to prevent new disaffection in the future. Occasionally, the simply set up new governments with officials friendly to Athens. Some allies were persuaded or coerced into adopting the Athenian system of money and Athenian weights and measures so that they would find it easier to trade with Athens than with other states.

Finally, in 454 B.C., the Athenians arbitrarily moved the headquarters of the league from Delos to Athens, where it would be more secure. They insisted that a part of the money collected for military purposes should be paid to Athens for guarding the treasury. With this event, the Delian League ceased to be an alliance and became instead an Athenian empire.

The ultimate results of the high-handed Athenian policy in the Delian League were first the destruction of the Athenian Empire, and in the long run, the destruction of the polis as the main form of government in Greece.