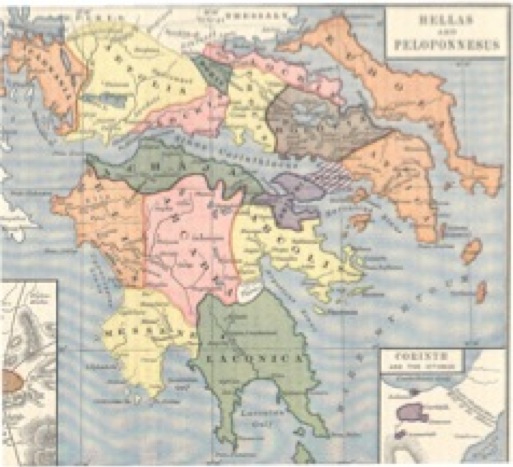

The Spartans inhabited an area called Laconia in the southern part of mainland Greece on what is called the Peloponnesus (see map). Laconia is ringed by hills, but most of the land area is dominated by one of the few rivers of any size in Greece, the Eurotas River. As it flows down from the north, the Eurotas has created a broad flat flood plain which is relatively open. This means that Sparta had more good, usable farmland than almost any other polis in Greece proper. When you add this to the fact that there are no really good harbors in Laconia, you will see why the basis of Spartan economy was farming until very late in her history. This also helps to explain why the headquarters of the polis was not on the sea, but right in the middle of the valley far from the coast.

This headquarters was a village, or rather, a collection of villages known as Sparta. There were a few temples and other large buildings, but Sparta never became a real city in the physical sense of a large settlement. Nevertheless, it was the center of a city-state, and that city-state was not called Sparta or Laconia. It was named after those who made up the polis – the Lacedaemonians. The Lacedaemonians and other peoples of Laconia were all Dorians. They spoke the Doric dialect. So there were probably Greeks who came to Laconia in the early Iron Age.

In the 700s and the 600s, when farming was still the main way of making a living in Greece, the Lacedaemonians were quite advanced in most respects. But when commerce became more important, they fell behind and retained a form of organization which seemed very primitive in later times.

Lycourgos and the Organization of the Spartans

Now that we have a notion of the conditions under which the Lacedaemonians lived, let’s look at their organization. We don’t know what the polis was like in the 700s, but by 600, it reached a point where it did not need to change thereafter. That is the organization that I wish to discuss.

The constitution of the Lacedaemonians is attributed to a Spartan leader named Lycourgos who ruled in the early 700s B.C. The executive branch is the most unusual part because the Spartans continued to have a basileus. In fact, they had two of them. In most places, remember, the basileus disappeared. Maybe the fact that there were two kings helped to preserve the institution in Sparta. This post was hereditary in two families. That is, one basileus came from one family and the other came from the other family. Normally, they ruled for life. As in the Dark Ages, their job was to lead the army in war and to perform certain religious ceremonies. They had no other official responsibilities.

Other officials handled the other executive duties. There were five of these men, and they were called ephors. The world ephor means overseer, and one of their jobs was to accompany the king and see to it that he did not abuse his authority. They could recommend that a basileus be deposed and replaced by one of his relatives. The ephors were elected each year from the whole body of citizens, and they could not succeed themselves in office.

The Spartan council was called the gerousia. Gerousia means old men. To serve on this council, a man had to be at least sixty-years-old. There were twenty-eight members of the gerousia, and they served for life. When a member died, the remaining members nominated several candidates to replace him, and his successor was chosen by a voice vote of the assembly. It was the gerousia that decided if the basileus should be replaced, and it also decided what the assembly would discuss and vote on.

The assembly, which did all the electing and other decision-making, was made up of all adult male citizens. They all had the same political privileges, with the exception of the kings. They could hold any elective office. Moreover, they were economically the same. The lands of the polis were all held in common. Spartans had some private family property, but most ot the land was allotted to citizens by the state. Spartans no real monetary wealth – Lycourgos had banned money. Well, that isn’t exactly true. He didn’t ban money, he just ordained that the Spartans would henceforth use iron coins instead of gold, or silver or copper. Iron coins have no real international trade value and they are very heavy, so Spartan money would be useless anywhere but Sparta. Each citizen family was given a plot from which to maintain itself. So the members of the assembly are sometimes called “equals.”

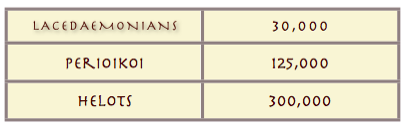

Now this might seem to be an equitable system, but the problem with it was that not every inhabitant of Laconia was a citizen of the polis. Out of an estimated population of 450,000 persons in 450 B.C., only 30,000 were members of the citizen families.

About 125,000 persons were what Spartans called perioikoi – those who live around. These were probably inhabitants of outlying farms and villages that were taken over by the Spartans when they expanded in Laconia. These persons were free, and they were even allowed to hold land and other private property. They held office in their own towns. They paid taxes and served in the army, but they did not have any political rights of citizens.

The remaining 300,000 inhabitants were called helots, and they belonged to a group apart. The helots were slaves belonging to the state, and they had no rights at all. They were assigned to the common land owned by the polis, and they did all the work on Spartan farmland. Because the helots were exploited by the Lacedaemonians, there was always a chance that they might revolt and destroy the polis. The only way the Spartans could control them was with a strong army. Thus, all life in the city was oriented toward the military.

Not every inhabitant of Laconia was a citizen of the polis. Out of an estimated population of 450,000 persons in 450 B.C., only 30,000 were members of the citizen families.

Growing Up Spartan

As soon as a child was born in Sparta, the mother would wash it with wine in order to make sure that it was strong. The child was brought by his father to the elders, who carefully inspected the newborn infant. If they found that the child was deformed or weakly, they threw it off of a cliff. Until the age of seven the child was reared by his mother. At the age of seven, every Spartan boy left home and went into a military training program called the agogé. They lived, trained and slept in their the barracks of their brotherhood. At school, they were taught survival skills and other skills necessary to be a great soldier. School courses were very hard and often painful. Although students were taught to read and write, those skills were not very important to the ancient Spartans.

Only warfare mattered. The boys were not fed well, and were told that it was fine to steal food as long as they did not get caught stealing. If they were caught, they were beaten. They boys marched without shoes to make them strong. It was a brutal training period.

Legend has it that a young Spartan boy once stole a live fox, planning to kill it and eat it. He noticed some Spartan soldiers approaching, and hid the fox beneath his shirt. When confronted, to avoid the punishment he would receive if caught stealing, he allowed the fox to chew into his stomach rather than confess he had stolen a fox, and did not allow his face or body to express his pain.

They walked barefoot, slept on hard beds, and worked at gymnastics and other physical activities such as running, jumping, javelin and discus throwing, swimming, and hunting. They were subjected to strict discipline and harsh physical punishment; indeed, they were taught to take pride in the amount of pain they could endure.

The typical Spartan may or may not have been able to read. But reading, writing, literature, and the arts were considered unsuitable for the soldier-citizen and were therefore not part of his education. Music and dancing were a part of that education, but only because they served military ends.

Unlike the other Greek city-states, Sparta provided training for girls that went beyond the domestic arts. The girls were not forced to leave home as boys were, but otherwise their training was similar to that of the boys. They too learned to read and write, to run, jump, dance, throw the javelin and discus, and wrestle. In many such activities, Spartan women would practice naked in the presence of their male counterparts and women who excelled in physical activities were respected for their athletic feats. With their husbands confined to barracks or on active service, and frequently called up for campaigns or required to take part in political and civic duties, it was left to Sparta's matrons to run the estates. Spartan wives administered the family wealth—and, thus, in effect, the entire Spartan agricultural economy. A Spartan citizen was dependent on his wife's efficiency to pay his "dues" to his dining club. This economic power is in particularly sharp contrast to cities such as Athens, where it was illegal for a woman to control more money than she needed to buy a bushel of grain.

Somewhere between the age of 18-20, Spartan males had to pass a difficult test of fitness, military ability, and leadership skills. Those who survived it continued with their military education and were enrolled in the local militia. If they passed the tests, they might also be elected into a particular mess. The mess was a local dining facility, military unit and club. This is where Spartans would eat the main meal of the day for the rest of their lives. If they were not elected to a mess, they were not worthy to be Spartans and would usually leave the country or commit suicide out of humiliation.

After eleven years of training, the young man entered the army itself at 18, and he served on active duty until he became 30. After age 30, the man would marry, have a family, and participate in government. If he did not find a wife, a suitable Spartan woman would be found for him by the state. The state would then provide the family with land and helots to work that land. But even then, he was still a soldier. Every man over 30 was still required to eat the main meal each day with the other men in his military mess, rather than with his family. In time of war, of course, all men served as long as they were physically able to do so. This military organization gave the Spartans the power it needed to keep the helots under control.

Sparta in the Greek Context

The internal organization of the Spartan polis gave it great strength and helped to determine the role it would play in the Greek world as a whole. The Spartan military system gave this polis an enormous advantage militarily over the other city-states of Greece. In most Greek city-states before 400 B.C., the armies were essentially militia forces made up of the citizens of the community. The fighting men were not professional soldiers. They were farmers, craftsmen, and merchants.

In Greece, crops are planted in early fall and harvested in the spring. Wars were fought in the summertime when there was not a lot of work to do on the farms. Thus, the armies would fight in the summer and then go back home to farm or to make a living in some other way. This was necessary because they did not receive any pay for fighting. In most cities, the soldiers were strictly amateurs who were not well trained for war.

But in the polis of the Lacedaemonians, the situation was quite different. The Spartans did not have to work on farms, because the helots did all of the work for them. They were soldiers all the time and throughout their entire lives. They were trained for military life from childhood onward. They were much better drilled, much better disciplined, and much more willing to fight than the soldiers of other city-states. This gave them such an advantage that for 300 years no other polis was able to defeat them seriously in battle.

You might imagine that the Lacedaemonians were so much more powerful than the other city-states that they would simply conquer all of Greece and bring it under their power. But this was not possible. Very early the Spartans realized that they would destroy themselves if they tried to conquer the other Greeks. They could send armies to beat any other polis, but to hold on to anyone they conquered, they would have to leave soldiers in the conquered cities for long periods of time. They could not do that because they had to keep the army at home to guard the helots.

Thus, they developed a semi-isolationist policy in foreign affairs. To protect their immediate frontiers, they entered into a mutual defense alliance called the Peloponnesian League with the neighboring states in 550 B.C. It included most of the states in the large peninsula known as the Peloponnesus. Outside the Peloponnesus, they tried to maintain a balance of power with a limited commitment of troops. If any Greek states felt threatened or coerced by its neighbor, it could appeal to Sparta for assistance. The Spartans often responded to complaints with threats and war if necessary.