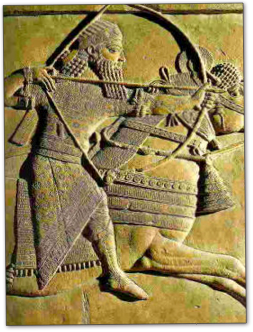

By the early 800s, the Assyrians had developed into an Iron Age civilization. Between 850 and 650 B.C., they brought all of the lands of Mesopotamia under their control. This conquest was the work of several powerful and warlike kings, but perhaps the most important of them was Tiglath-Pileser III who ruled from 744-727 B.C. and amassed a large empire.

The reasons for this conquest are to be found largely in the character of the Assyrian people. Simply put, they loved warfare and conquest. Their kingdom was located at a crossroads between Mesopotamia, Asia Minor, and the lands of Syria and Palestine. Thus, the Assyrians had been threatened by enemies on all sides. This situation had made warfare a way of life for them, and had nurtured in them both a toughness and a love of war.

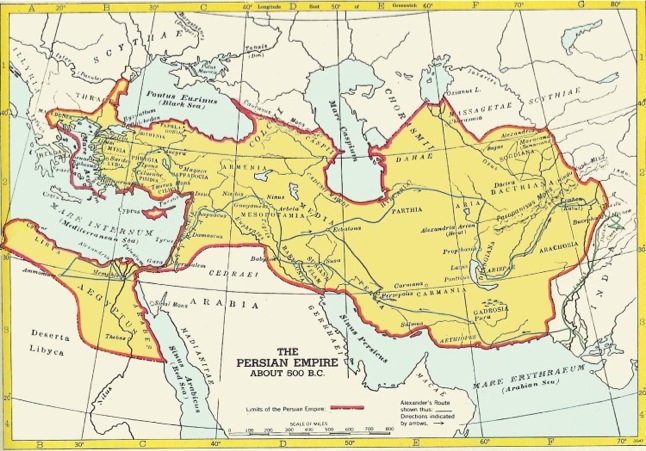

Despite its rapid growth and size, the Assyrian Empire lasted longer than earlier imperial systems, so we should consider the reasons for its success. The Assyrians created a unified government to rule their subjects. In many areas the older governments of subject states were replaced with Assyrian officials who administered them for the king. The Assyrians adopted brutal measures to suppress the opposition and prevent revolt. A good example of their policy was the treatment of Israel. The Assyrians conquered the northern Hebrew kingdom in 722 B.C. Hebrew leaders were exterminated, and many of the people were carried off into slavery to Assyria. Ten of the Hebrew tribes virtually disappeared. They are the famous Lost Tribes of Israel. The Assyrians did not behave toward the Hebrews in this way in response to Hebrew opposition, they did so to avoid future difficulties with the newly conquered Hebrews and as an example to other peoples they controlled. These oppressive policies went far to prevent serious revolts for a long time; but they made Assyrian rule so unpopular that the subjects were bound to rise up if the Empire were ever to weaken for any reason.

After 650 B.C. it did weaken. From 626-612 B.C., there was a great revolt in the Empire. It ended with the total destruction of Assyrian power. With the fall of Assyria, political preeminence in Mesopotamia passed once again to the old imperial city of Babylon, which now enjoyed a brief period of resurgence. From 612-539 B.C., Babylon was ruled by a people known as the Chaldeans. Thus this empire is sometimes called the Second Babylon Empire, or the Chaldean Empire. The Chaldeans had been the chief leaders of the insurrection against the Assyrians, and when the revolt was over, they went on to seize a large part of the old Assyrian Empire for themselves. This was a relatively easy task because the long Assyrian rule had already eliminated or tamed many of the states that might have offered the Chaldeans much opposition.

The greatest of the Chaldean rulers was King Nebuchadrezzar II (ca. 605-560 B.C.). He is famous because he attacked and destroyed the remaining kingdom of the Hebrews (Judah) in 587. He treated the tribes of Judah almost as badly as the Assyrians had treated the Israelites. He drove most of them out of their homeland and forced them to live in Mesopotamia near Babylon. Nebuchadrezzar thought that once the Hebrews were resettled, they would be absorbed into the general population of Mesopotamia, and thus disappear as a cultural group. It might have worked if the Chaldean Empire had lasted longer.

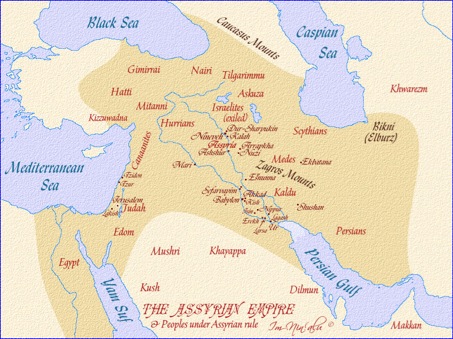

A new power that suddenly burst into the Near East in the 500s B.C. This was the last of the great Near Eastern Empires – the Empire of the Persians – that lasted from 550 to 332 B.C. The Persian Empire had its center in the high arid mountain region east of Mesopotamia. This region is know as the Iranian Plateau, and it corresponds roughly to the modern country of Iran. The region gets its name from the large group of related barbarian tribes that migrated into it from the north in the beginning of the Iron Age (about 1000 B.C.). At first the various Iranian tribes were independent, only tied together by a common language (which is Indo-European) and culture. The Persians were only one of the many Iranian tribes. But the Iranians began to acquire a more civilized way of life because of their contact with Mesopotamia.

Politically, the Iranians remained weak as long as they were divided into independent tribes. But a Persian leader, Cyrus the Great (550-530), united all of the Iranian tribes behind his leadership, and then they proceeded to conquer all of the mountain territories from Pakistan to the Aegean Sea. In 539, Cyrus descended into Mesopotamia and captured the city of Babylon. With the Chaldean Empire in his control, he was able to amass an enormous empire. The only question was, could he organize it so that he could protect it from internal opposition.

Cyrus divided the empire up into provinces called satrapies. They were large areas intended to cover territories with common political and cultural traditions. There was one for Mesopotamia, for example. Each satrapie had a governor called a satrap. He was usually a Persian at first, but later he sometimes came from the local population. The satrap had a complete government of his own, with a full staff to assist him in governing his province. In time of unrest in the Empire, the satrapie could operate autonomously without assistance from above. Within limits the satraps were free to adopt and develop independent policies for their provinces in keeping with local interests and traditions. In deference to local customs, the Persians practiced complete religious toleration. For example, Jewish leaders were permitted to return to Judah and rebuild the great temple to their Hebrew god.

The chief danger to the Persian administrative arrangements was that the satraps might become too independent and threaten the Empire. Several steps were taken to prevent this turn of affairs. Certain key members of the satrap’s staff were directly appointed by the king and were responsible to him. The Persians built an extensive road system to tie the Empire together, and created a messenger system – a kind of pony express – to keep the capital informed about what the satraps were up to. Finally, the king maintained a large army. This army not only defended the Empire from enemies without but also could be employed to control the individual satrapies. The Persian Empire was powerful and well organized, but it was far less oppressive than the Assyrian Empire had been.