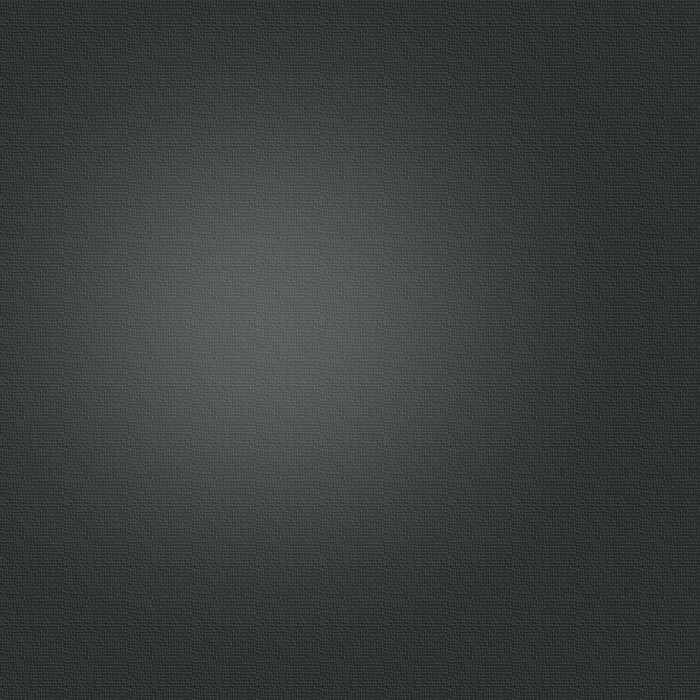

The Hellenistic World

The death of Alexander the Great marks the start of the later period of Greek history that scholars call Hellenistic Times. The period extends from 323 to the founding of the Roman Empire in 30 B.C. The death of Alexander set off a civil war among his Macedonian generals to see who would rule after him. In the war, his great empire broke up into several pieces each ruled by one of his generals. There were three major kingdoms covering Macedonia and large parts of what had been the Persian Empire. Some smaller states also existed. They remained independent in theory, but they were usually under the thumb of one or another of the larger states. Most old Greek city-states were in this category. So, let’s start off with a brief look at the political divisions of the Hellenistic world.

There were three major states:

Egypt: Rulers were descended from Ptolemy I, one of Alexander’s generals. This state included Egypt, part of Arabia, Palestine and the island of Cyprus. The new Greek rulers inherited a tightly-knit well organized bureaucracy, the ancient Egyptian tradition that rulers, the Pharaohs, were divine, and vast agricultural resources. This was the wealthiest of the Hellenistic States.

The Seleucid Kingdom: Founded by another of Alexander’s generals, Seleukos. This kingdom included most of what had been the Persian Empire proper – Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, and Iran. It grew and shrank considerably over its period of existence. It was the most culturally diverse empire, and had to be ruled with a strong hand. The Seleucid empire was only controllable through a strong bureaucracy and a powerful military.

The Antigonid Kingdom: After a period of chaos as one Greek general after another tried to acquire the Macedonian homeland, order was finally restored by members of the family of Antigonos Monopthalmus (one -eyed). Antigonos’s descendents ruled Macedonia and part of Northern Greece. This was the only completely Greek kingdom of the big three.. The Antigonid kingdom was weaker than the Seleucid kingdom, poorer than Egypt, but it was the most unified, and more militarily powerful.

Until about 201 B.C. these three great states maintained a precarious balance of power, and this made it possible for smaller states to exist, primarily by playing diplomatic alliance games with the larger states. Smaller states made alliances with the larger ones in order to maintain their independence, playing one great state against the others. There were some surviving Greek city states that we already know — Athens, Sparta, Rhodes — and a few rising city states in Asia Minor. These states also formed leagues to defend themselves.

In these states, big and small, the military was also Greek. It was recruited from Greeks who lived in each specific state and beefed up with Greek mercenaries who traveled to the state that paid the best wages. In fact Hellenistic mercenary units were highly specialized, well trained, well organized and negotiated with rulers for their pay and benefits. Some battles were decided on the basis of who could buy out the army of whom. Hellenistic armies fought on the Macedonian pattern. Hellenistic armies tended to be large by classical Greek standards, as many as 30,000 men in phalanx formation, with as many as two thousand cavalry. The infantry employed the long spears and lighter armor that Alexander had made the standard. [explain if necessary]

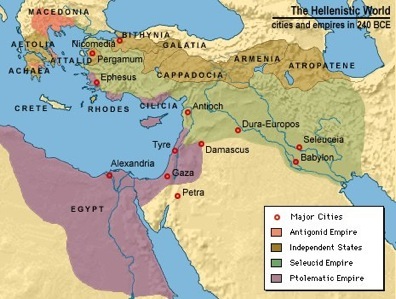

The great Hellenistic states were kingdoms. The office of king was hereditary and the king embodied the state. This was not like that old Greek idea of the basileus whose power was constrained by other government institutions. There were no checks on the power of a Hellenistic monarch. Each ruler was assisted by a large and elaborate bureaucracy that increased the king’s control over his kingdom. So, we can say that foreign absolute rulers dominated local populations through the use of a network of bureaucratic officials and a foreign army.

It is important to remember that in the non-Greek kingdoms, the majority of the resident populations were not Greek. But, the ruling families were Greek, and the ruling classes were either Greek or were natives who had acquired the language and cultural trappings of “Greekness.” The upper classes of the Hellenistic states and the urban populations had, by the mid-200s b.c., become thoroughly hellenized.

This meant that a profound change took place in the older Near Eastern lands like Egypt and Mesopotamia. Most of the people in these lands came from the older civilizations. They were Egyptians, Persians, or Jews for example. But the rulers, from the kings on down in government, were all Greeks and Macedonians. The governments were made up of foreigners. Non-Greek natives could get into government only by becoming Greeks. They had to give up their own customs, learn the Greek language, wear Greek clothes, and generally live and think like Greeks.

In the Hellenistic period, professionals, scholars and thinkers moved to wherever there was a demand for their work. Thus, we can say that scholars had, for the first time in the West become professionals who literally chased jobs and went where the money was, like scholars do today. Many of them were attracted to the new Macedonian kingdoms of the Near East. Hellenistic rulers founded lots of new cities in the Near East and encouraged Greeks to migrate to the cities and settle. The most famous city was Alexandria in Egypt, but there were many others. In these cities, the kings established Greek schools to educate the children of Greek immigrants and to teach Greek culture to their non-Greek subjects. The kings were willing to pay writers and philosophers to come to the cities to teach, write, and do research in the schools. Since they had a lot of money, they could attract the best scholars.

Greek culture spread all over the East, and intellectual activity became truly international not local as it had been before. In Hellenistic times, a new Greek dialect developed that was the same everywhere. It was called koine, common Greek. It was used by all educated men whether they were Greek or not. But it was not just language that spread. Greek literature and art, and to some extent, Greek thought replaced others for centuries.

Second, this universal culture (oikomene – the civilized world) chiefly belonged to educated members of the upper classes. It was not shared with the masses. In this respect, it differed from earlier Greek culture.

Because Hellenistic civilization was primarily for educated men, the quality of intellectual endeavor was significantly changed. Because there was so much organized research and study, considerable advances were made in knowledge, especially in natural science which would have held little interest for the earlier Greeks. For instance, Eratosthenes (d. 200 B.C.), a scholar at the Museum, calculated the circumference of the earth, missing the actual average by less than 200 miles. But, generally speaking, Hellenistic thought was not as profound or as universal in its appeal as early Greek thought had been. And it still is not to us today.

It is into this world that a new player in the civilization game would appear in the mid-200s B.C. -- ROME.

Coins of Hellenistic kingdoms:

right: Seleukos I shown in the “Alexander motif” with Zeus as victorius king on obverse. Below Right, Antigonid king.

Below: a gold coin of Ptolemy IV Eurgetes, stressing his control of the seas (Poseidon’s crown and trident). The obverse symbolized the plenty of Egypt.