Roman Expansion

What were the benefits of expansion?

Romans, like other ancient peoples took spoils from their defeated enemies. In the early period of Rome’s development the most important spoils that Romans took from their enemies was land. Rome seldom had enough land to provide for all of her citizens. They were not seafarers, so they couldn’t solve the problems of land shortage through colonization or trade like, say the Athenians. So, Roman settlements had to be in Italy, and that meant that they had to take land away from some other state to achieve that goal. Roman politicians knew that they could relieve population pressures at Rome by fighting to gain more land, so political leaders, who were also, you remember, military leaders actively sought wars.

But economic motives weren’t the only ones. The causes of expansion were more complex than simply wars for land. Conditions in Italy in the Early Republic made it almost impossible for Rome or any other state to avoid war. There were literally hundreds of small, independent states in Italy, all competing with one another for limited resources. Most of these states needed land, and they could only get it by taking it from their neighbors. So, war became a regular feature of Roman life at a very early stage in its development. Roman virtues were warrior virtues that were appropriate to farmers and warriors. In order to acquire those virtues, men needed to fight wars. Thus, one major benefit of expansion was glory! If a consul won a great battle his prestige increased. He and his relatives would find it easier to win election to offices in the future and would be given greater military responsibilities. Even common soldiers earned great prestige when they had fought in an important Roman victory. They received land and a share in the spoils of war. Thus, the Romans were always ready and even eager to fight, if they were given any reason to do so by some other state. And conditions were such that reasons could usually be found.

Another important reason for Roman expansion is also related to the frequency of warfare in the early period of Rome’s development. Romans were used to viewing their “next-door neighbors” as potential threats to the security of the Republic. As Rome expanded in Italy, she bumped into yet another quarrelsome neighbor that wanted her land. Hence, the unwritten assumption of Roman Foreign policy became “every neighbor is yet another potential threat.”

Rome’s earliest conquests can be neatly divided into three parts -- the conquest of central Italy, the conquest of northern italy, and the conquest of southern Italy. We begin with central Italy. From 500-400 Rome fought primarily against hill tribes and nearby cities in Central Italy. Basically they did so to protect themselves. These tribes or these other cities raided Rome, and Roman soldiers would go out and try to conquer them. And to make sure that they would not be threatened again, Rome would settle some of her own citizens among these people. In other words, the Roman citizens would receive land, settle down, and form communities of their own or intermarry with the locals. What this means is that Roman settlements are now farther away from Rome proper, and they have to be protected as well – which means more expansion.

In the 390s another threat appeared, this time from the north. Tribes of Celts – called Gauls – began to raid into Central Italy, and the Romans organized resistance among the other Italian cities to these raids. By 350 BC the Romans were able to defeat the Gauls and establish their authority over northern Italy.

In 282 B.C. the Romans received an appeal from some of the old Greek cities in southern Italy to assist them in resisting one of the lesser Hellenistic kingdoms, that of Epirus. The Romans agreed to provide that assistance and fought against the king, named Pyrrhus, until 275 when they not only defeated that king but essentially brought all of southern Italy under their influence. So, by 275 BC the Romans controlled all of Italy.

By 275 the Romans controlled all of Italy, and in 264 began the great wars that allowed Rome to become master of the Mediterranean. The most important of these wars were called the Punic wars, which came in three parts. The first lasted from 264 to 241 B.C., and the second from 218 to 201 B.C. The third led to the destruction of Carthage in 146 B.C.

These wars were fought against the city of Carthage, an old Phoenician colony (Punic is another word for Phoenician) on the northern coast of Africa. In 264 Carthage was a lot like Rome. It was powerful, controlled a lot of territory, including Spain by the way, and wanted more. The reason for the war was actually quite simple. Rome and Carthage were the two big powers in the central Mediterranean. It just seemed inevitable that these two big powers would come to blows.

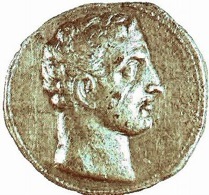

Pyrrus of Epirus

In the first war, most of the fighting took place on the sea around Sicily. The Romans were at a disadvantage because they had no navy. But they created several large fleets when they saw it was necessary. They borrowed ship designs from their Italian Greek allies, and probably employed them as rowers as well. They then modified their ships to turn sea battles into land battles. Roman loses were tremendous, but they finally won through sheer perseverance.

The chief feature of this Second Punic War was that the Carthaginian army was commanded by another one of those military geniuses of the ancient world, Hannibal. Hannibal decided to take the war to the Romans. Hannibal led his forces into Italy in 218 BC and proceeded to beat the Romans in battle after battle. But Hannibal could never accomplish two feats that were essential to defeat Rome. He could never take the city itself, and he could never get the other Italian cities to abandon their Roman allies. Those policies we talked about of giving lots of rights and independence to the Italian cities really paid off in the Punic Wars.

Rome and Carthage before the First Punic War

Every time the Romans fought a battle with Hannibal they lost. So they decided to harass his army as it marched up and down Italy. In other words, they wore him out. Then in 204 BC, a Roman army under a famous commander by the name of Scipio Africanus landed in Africa to threaten Carthage itself. Hannibal was forced to leave Italy and defend his home. At the Battle of Zama, near Carthage, the Romans defeated him for the first time. Hannibal fled to the Hellenistic kingdoms of the East and Carthage surrendered. Rome was now the chief power of the central Mediterranean.

After Zama, the king of Macedonia, Philip V, welcomed Hannibal to his court. Hannibal assured Philip that the Romans had expended so many men and resources defeating Carthage that Philip could pick up some territory. On Hannibal’s advice, Philip began to put pressure on the Greeks who complained to Rome.

The Romans put Scipio in charge. Scipio raised an army, and, in what is called the Second Macedonian War, 200-196 B.C., he crushed Philip. The Punic Wars had not in fact weakened Rome but given it a large, experienced fighting force led by truly able commanders.

After the Romans defeated Philip, the Seleucid king, Antiochus III, thought, “Hey, the Antigonids are weak, so that gives me an opportunity to expand my power in Greece.” (Hannibal was now with him as well -- he would commit suicide in 183 BC) So, in 192 BC he began to annoy Rome’s Greek friends. The Romans asked Scipio to go to work again, and he defeated the Seleucid army (The Syrian War, 192-189BC).

Above: Philip V of Macedonia

Below: Antiochus III of Syria

So, between 204 and 188 B.C., Rome became the big power in the Mediterranean basin. Now, I should mention that the Romans didn’t annex any of these defeated states yet, they just charged them big fines and told them to behave. The extent of Roman Expansion up to now outside of Italy had been the acquisition of Spain from Carthage, and that’s about it. Rome was not the great empire that she would become, but, Rome had changed as a result of all of these wars, and not necessarily for the better.